Ballet’s Colonial Legacy

Ballet's Colonial Legacy: The Politics of Dance in the Age of Empire

Ballet, an art form steeped in the courts of Renaissance Europe, is widely admired for its technical precision and elegance. Yet its role in the history of colonialism is often overlooked. As European powers expanded their empires in the 18th and 19th centuries, ballet was exported as part of the broader cultural imperialism that sought to reshape colonized societies. In many ways, it became an instrument of domination, reflecting and reinforcing European ideals at the expense of indigenous cultures.

A Cultural Weapon

European colonialists did not merely impose political control—they also sought to establish cultural dominance. Ballet, with its origins in the aristocratic courts of France and Italy, was part of this civilising mission. It was viewed as the pinnacle of European sophistication, a marker of “high” culture. In contrast, indigenous dances, with their improvisational structures and communal rhythms, were often dismissed as “savage” or “primitive.” This binary of “civilized” versus “savage” was a key component of the colonial worldview.

In places like South Africa, where the apartheid government rigorously promoted European cultural forms, ballet was weaponized to reinforce racial hierarchies. As dance scholar Brenda Dixon-Gottschild observes, the very structure of ballet—the straight spine, contained movements, and verticality—mirrored European ideals of discipline and control. These traits were juxtaposed against the perceived looseness and rhythmic complexity of African dance, which was often suppressed under colonial rule

Suppression and Resistance

The suppression of indigenous dance was not an incidental outcome of colonialism; it was a deliberate strategy. In South Africa, indigenous dances were regulated and, in some cases, banned altogether. This reflected the anxiety of colonial rulers who feared the power of communal gatherings, where dance played a central role in cultural and political expression. By contrast, ballet was encouraged as a symbol of order and “civilization”.

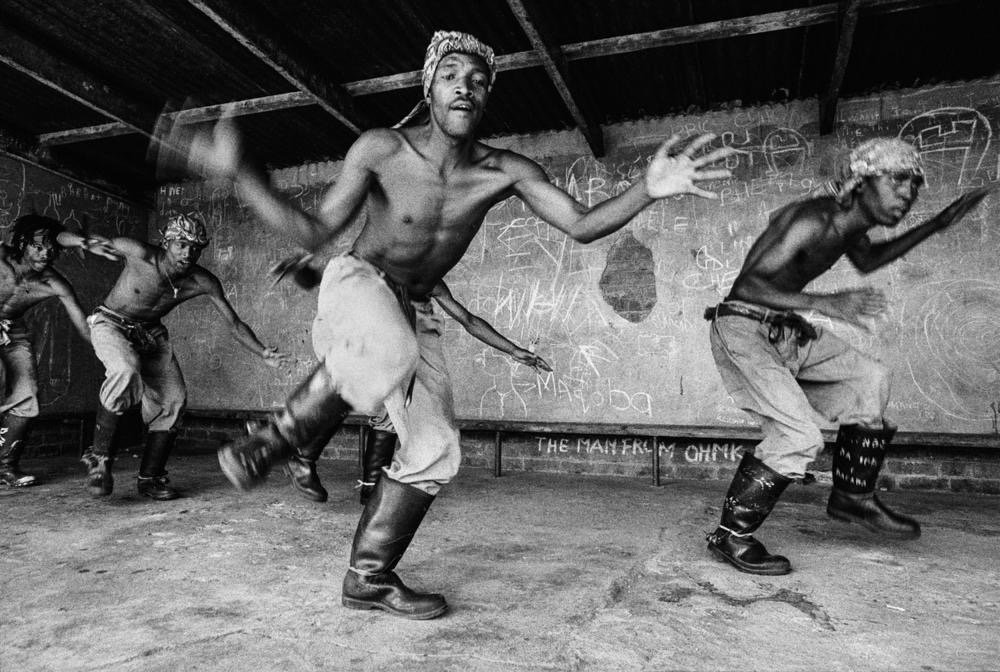

However, dance also became a vehicle for resistance. Black South Africans, for example, used dance as a form of political protest during apartheid. The Gumboot Dance, developed by migrant mine workers, became a symbol of defiance. While ballet was used to control and suppress, indigenous dance forms were harnessed as tools of empowerment and identity.

“Gumboot Bapedi” by Ruth Seopedi Motau, Soweto, 1993

The Colonial Legacy in Ballet Education

The legacy of colonialism is still visible today, particularly in the realm of dance education. Ballet continues to be privileged in many Western institutions, with African, Indigenous, and other non-Western dance forms often relegated to elective status. Dance scholar Nyama McCarthy-Brown points out that this hierarchy of value is a direct continuation of the colonial mindset, where European culture is deemed superior and non-European traditions are marginalised

In North America and Europe, ballet remains the bedrock of most formal dance education, despite the increasing recognition of its colonial roots. This has led to calls for the decolonisation of dance curricula, with scholars advocating for a more inclusive approach that values a diversity of forms. Yet the dominance of ballet persists, particularly in elite institutions, reflecting the deep entrenchment of Eurocentric values.

Decolonizing Dance

Efforts to decolonize ballet are underway, but they face significant challenges. Some choreographers are incorporating Africanist elements into their work, while others are questioning the structures and aesthetics that underpin the form itself. However, as McCarthy-Brown notes, true decolonisation requires more than just surface-level changes. It demands a fundamental rethinking of how dance is valued, taught, and performed

In recent years, there has been a growing recognition of ballet’s colonial legacy, particularly among scholars and practitioners who are re-examining the art form’s history. This has sparked debates about how ballet can evolve in a way that acknowledges its past while embracing a more inclusive future.

Mamela Nyamza’s Radical Reimagining

Mamela Nyamza, a South African choreographer known for her radical reimagining of dance, uses ballet as a medium to critique and deconstruct the colonial imprints embedded in the art form. In her performances, Nyamza reframes classical ballet through an African lens, incorporating elements of African dance, social commentary, and embodied resistance to challenge Eurocentric ideals of beauty, discipline, and control.

For example, in works like "Hatched Ensemble", Nyamza disrupts the rigidity of ballet’s aesthetics by blending it with traditional African movements and feminist themes, drawing attention to the socio-political dynamics of race, gender, and power. Through her bold fusion of forms, she reclaims ballet as a space for African expression, using it not only to confront its colonial legacy but also to create a new narrative that celebrates African identity and culture.

“Hatched Ensemble” is currently showing at The Barbican Theatre in London from 9 to 12 October. I’ve got a juicy £15 promo code that you can find here. The show is my dance show of the month and is part of Dance Umbrella, London’s International Dance Festival.

“Hatched Ensemble” by Mamela Nyamza. Image by Mark Wessels

Final Thoughts…

Ballet's history is inseparable from the history of colonialism. While it remains one of the most celebrated art forms in the world, its role in reinforcing cultural hierarchies and suppressing indigenous traditions cannot be ignored. As the movement to decolonize dance gathers momentum, the challenge lies in reimagining ballet not as a relic of European imperialism, but as a living art form that can be enriched by the diverse traditions it once sought to exclude.

The enduring legacy of ballet in the colonial context is a reminder that cultural imperialism was as much a tool of conquest as military or economic domination. As we move forward, acknowledging and addressing this history is crucial in building a more equitable and inclusive future for the arts.